About a decade ago, I began using a website called Facebook. At the time, it was simply a MySpace with a cleaner appearance; no gaudy personalized backgrounds on pages autoplaying insufferable music while crappy web animations crowded the screen. Today, it scarcely resembles what it was then. It has grown into a kind of launchpad for Internet use, a portal into the world beyond its confines. Facebook is no longer a catalogue of capricious moods and ephemeral interests and poorly-lit snaps of cats or what your cousin ate for lunch.

Social Media is a direct line into what other people are interacting with online. When a celebrity dies, a disaster strikes, or a Washington scandal breaks, more and more of us learn of these things from Facebook or other social media sites. Indeed, in May of 2016, a report by the Pew Research center found that 62% of Americans get their news from social media; nearly half of all Americans get it primarily from Facebook. Twitter, Reddit, and YouTube also have high numbers of users who claim to get all or most of their news from these sites. There’s an inherent problem with this: Social media creates insular ideological bubbles.

It’s no secret that Facebook curates your news feed, trimming down what you see, cherry picking what the algorithm deduces you’ll want to see and weeding out the rest like a prom queen plucking errant eyebrow follicles. Facebook does this primarily because of volume; if given an unfiltered news feed, you would be so swamped with posts you don’t want to see that you’d likely miss those important to you. Imagine not seeing your best friend’s post that she’s engaged because it was buried under all those “Type Amen If You Love Jesus” posts and dank memes disseminated by a middle school classmate you barely remember. In 2014, Facebook engineer Lars Backstrom, whose name suggests he missed his calling as the lead guitarist in a Viking metal band, explained that “Facebook’s news feed algorithm boils down the 1,500 posts that could be shown a day in the average news feed into around 300 that it ‘prioritizes.'”

The algorithm makes choices based on how often you interact with its poster, via comments, likes, reposts, personal messages and so on, as well as how many overall likes, shares, etc. the post gets. It also analyzes how often you’ve viewed similar material. Finally, it factors in how often a post is hidden by users in your friends network.

Think about that for a moment. A friend posts a news article and his commentary on it. You give it your virtual thumbs up, maybe comment or share his post. More of his posts appear in your feed. Since his posts are now prioritized, you’re naturally more likely to “thumbs up” more of his posts than you are those posts that have been filtered out, so his future posts are further prioritized, creating a feedback loop with those with whom you are most ideologically compatible. As these friends block various sources from their feeds, so too do they limit the likelihood that you will see them.

In an Amazon interview regarding his 2011 bestseller “The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding from You,” Eli Pariser said, “Your filter bubble is this unique, personal universe of information created just for you by this array of personalizing filters. It’s invisible and it’s becoming more and more difficult to escape.”

Social media is not the sole cause of American polarization, but it would be foolish to underestimate its effects on the trend. (And make no mistake, we are more polarized–according to surveys published last year in Science Daily that spanned from 1970-2015, more so than at any point in modern history; one might argue more so than at any point since Reconstruction. In a 2012 article in Oxford Academic memorably and mouth-numbingly titled “Affect, Not Ideology: A Social Identity Perspective on Polarization,” Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes showed that “both Republicans and Democrats increasingly dislike, even loathe, their opponents.” Similarly, last year Abramowitz and Webster, in ScienceDirect, showed that “since the 1980s, there has been a large negative shift in affect toward the opposing party among supporters of both major parties in the U.S.”)

We are now a country with historically high levels of animosity towards those on the opposite end of the political spectrum, and receiving news through a strainer that ensures that we have fewer and fewer interactions with those with whom we disagree.

Some sneak through, though. Aunt Bea or, more oddly, someone else’s Aunt Bea you’ve never met, leaves a disagreeable comment on your post.

We’re more likely in virtual spaces such as Facebook to be rude or outright vitriolic. According to a 2012 article in Scientific American, “Why is Everyone on the Internet So Angry,” a “perfect storm” of factors converge to create a more hostile discourse: anonymity or near-anonymity, a lack of general accountability, physical distance from those we argue with, the medium of writing itself (which better facilitates snark), the lack of real-time back-and-forth discussions enabling crafted monologues. These are just a few of the myriad factors at work.

One might add to this perfect storm the increasing unfamiliarity with the viewpoints of those on the filtered-out fringes of one’s “filter bubble” and the reinforcement of virtual thumbs-up from those who think like you, whom the bubble has sifted into your corner. As we have these digital sparring matches, it is inevitable that our opponents unfriend or hide us, or we them, which simply tightens the bubble.

All of this is bad enough, but it gets worse when we consider another aspect: where the information shared within the bubble comes from.

In 2013, the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication published an article called “Birds of a Feather Tweet Together: Integrating Network and Content Analyses to Examine Cross-Ideology Exposure on Twitter.” They found that “on Twitter, political talk is highly partisan, where users’ clusters are characterized by homogeneous views” and this clustering reinforces a move “away from neutral news sites in favor of those that match their own political views.”

It’s been argued, notably in an April 2012 article in the Washington Post, that the news in general remains relatively neutral; studies cited by the Post found that there was a slight left slant by major news outlets but that it was offset by more favorable reporting of conservative leaders, resulting in a kind of zero sum. The Post did go on to point out that viewers fail to distinguish between reporting and “opinion-mongering,” noting that the most popular shows on cable news outlets are those “in which opinionated hosts ask opinionated guests to sling opinions about the day’s news.”

However, the Post seems to miss the point. Perhaps there is an overall leveling, with all mainstream media canceling each other, but the average viewer does not consume news media in the aggregate. An October, 2014 report by Pew found that self-reported liberals and conservatives receive news through vastly different, distinct channels and networks. Particularly on the right wing, the number of reported “trusted” media outlets is sparse. People aren’t reading or watching a broad spectrum of news media. They have their one or two trusted sources and are growing more and more distrustful or dismissive of all other outlets.

These days, there are certainly enough politically-slanted news outlets, from Politico or MSNBC on the left side of center to Fox News or Breitbart on the right. The farther from center, the closer these “news” outlets resemble the rambling blogs of conspiracy theorists who save their fingernail clippings in pill bottles and line their Fruit of the Looms with tinfoil (lest the invisible lasers Obama shoots from space make them gay).

InfoWars perhaps best exemplifies this cusp; its bloated host, human skidmark Alex Jones, has broken “news” that the Sandy Hook school shooting was faked or that chemicals in juice boxes can turn straight people into homosexuals.

It’s difficult to even call InfoWars news in the traditional sense of the word, and Jones would be laughable if he weren’t taken seriously by so many. InfoWars reaches 6.5 million people monthly, not the least of whom is the current President, who has called into the show and praised Alex Jones.

The phrase “Fake News” has been co-opted by the current administration and its supporters as a means of discrediting any journalism that it disagrees with, so much so that I must take a moment to define the term as used here. Fake news is any publication that presents itself as journalism but is distorted or unsubstantiated; it is intentionally misleading and or inflammatory. Fake news, in this original sense, was a powerful force during the last election and remains a significant threat.

“Fake news is nothing new,” a November 2011 post on FactCheck.org begins. This is certainly true. Fake news comes in all forms from fairly innocuous (the kid who died when he ate Pop Rocks and drank Coca-Cola) to world-shaking (the Yellow Journalism that led to the U.S. entering the Spanish-American War).

It can be used for humor, as The Onion has done so well for so long. But there is a humorless, politically motivated form of fake news: baseless, intentionally manipulative, presenting itself as legitimate without the wink. The Telegraph in March of this year rightly characterized such “outlets” more as propaganda than satire. On Facebook, they have grown like ugly hipster beards; one minute virtually nonexistent and the next ubiquitous. “Bogus stories can reach more people more quickly via social media than what good old-fashioned viral emails could accomplish in years past,” FactCheck explains.

Indeed, there’s been an unprecedented explosion of Fake News in recent years. The Telegraph lays out why this is so: in the past, when print was the medium of choice for news, distributing fake news was prohibitively expensive for most. It was also far more difficult to build a core audience. Because this was the case, there were fewer instances, and therefore more risk of being noticed and sued. Today, there is an avalanche of misinformation issued anonymously, at virtually no cost. Click-based revenues make it profitable, and it spreads like wildfire.

David Mikkelson, in an 11/16 article on Snopes, defined “Fake News” as “fabricated stories set loose via social media with clickbait headlines and tantalizing images, intended for no purpose other than to fool readers and generate advertising revenues for their publishers.”

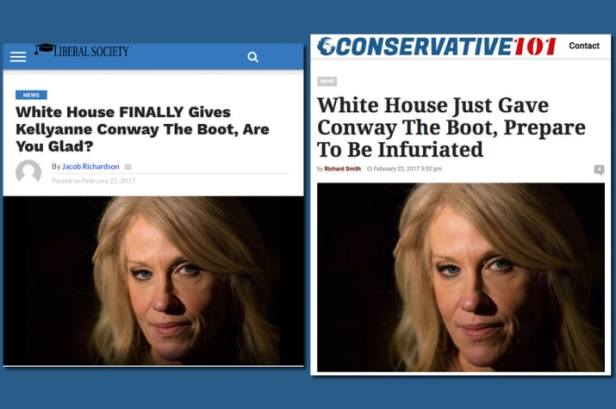

Indeed, this seems to be the case quite often; as Lindsay Ellefson notes in a 2/17 article on Mediaite.com, the ultra-conservative fake news site Conservative 101 and the uber liberal and equally fake news site Liberal Society are in fact owned by the same company, and the articles that appear in each are remarkably similar–just altered to suit the target audience.

However, as much as this is often true, Mikkelson seems to have missed an entire subset of fake news, that less concerned with revenue than with manipulating the public and swaying opinions.

In a 3/11/2017 article, the Huffington post reported on the “tsunami” of Internet trolls that plagued social media sites for Bernie Sanders’ supporters. The majority of these trolls were posting from outside the U.S. and they generally operated by posting fake news stories about Hillary Clinton designed to discredit her and foster anti-Clinton sentiments among Sanders’ base.

PBS, last December, ran an article following the so-called Pizzagate shooting (wherein a man, convinced by a fake news story regarding Clinton, a child sex-trafficking ring, and a pizza shop front, opened fire in said shop with an AR-15, thankfully killing no one) that cited a disturbing finding: “fake election news outperformed total engagement on Facebook when compared to the most popular election stories from 19 major news outlet [sic] combined.”

The FBI, as reported by AMP on March 21, 2017, is currently investigating the role of pro-Trump articles, including those from InfoWars and Breitbart, retweeted by a swarm of Russian twitterbots, had on the election and whether any of these outlets knowingly participated in this proliferation of their content.

What is the impact of this? The Economist published findings in February of this year that suggest that while fake news may have the effect of strengthening our polarization, it did not significantly sway the election. “The authors collected a database of fake news stories shared before the election and surveyed 1,200 Americans about them. These fake stories seemed very much slanted in favour of Mr Trump. In the three months before the election, Americans shared pro-Trump fake news stories 30m times on Facebook—almost four times more than false news favouring his opponent, Hillary Clinton. It seems that seeing was believing. Half of the people surveyed who viewed a fabricated headline believed it, compared to 10% of those who had not.”

That said, the study concludes that false headlines “might have contributed to the election outcome, but the evidence here does not suggest that it was pivotal.” Take that with a grain of salt; first, the study also showed that respondents remembered reading fake news stories that researchers invented as often as they remembered those that had actually appeared on social media sites. This cloudy recall casts doubts on the validity of the conclusions. Second, emphasis should be placed on the words “contributed” and “pivotal.” It is indeed unlikely that fake news was the essential force in the 2016 election, but it was a contributing factor, the impact of which should not be viewed singularly. The effect of the deliberate proliferation of misleading “news,” when combined with paid foreign hackers posing as Americans commenting online, twitter bots assailing posters, paid placement of propaganda embedded in legitimate articles, and so forth is much harder to quantify.

How organized, how influential, how targeted and deliberate was the spread of propaganda on social networks? That’s a question shrouded in uncertainty, obfuscated by sheer numbers. But a close examination of a company called Cambridge Analytica casts a disturbing light on the role of news-sharing and social media in the modern political environment.

[This piece continues in “Picking Up The Pixels, Part 2: Democracy Buys the Data FarmM”]